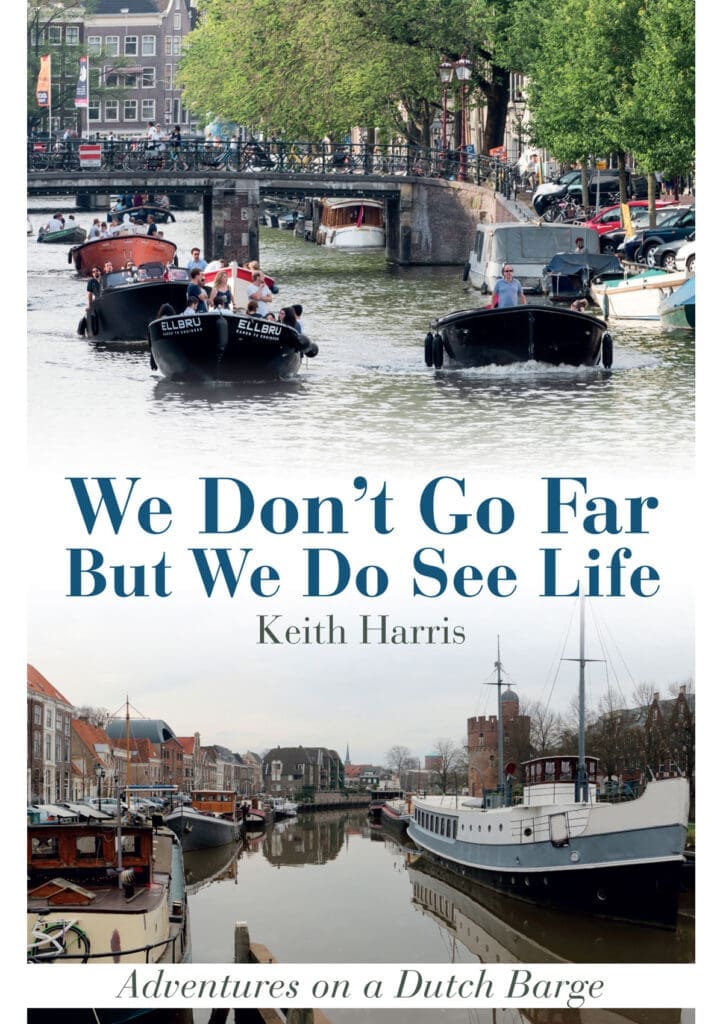

In this excerpt from his book, We Don’t Go Far, But We Do See Life, Keith Harris tells how he acquired his replica Dutch Luxemotor, Saul Trader, the characters he came to know, and putting on Folk On The Water festival.

If you enjoy this excerpt, you can read more in We Don’t Go Far, But We Do See Life.

For a limited time only, get the book for free with any print subscription to Towpath Talk (UK only).

Chapter 1 – Soul Trader

I always got bored over Christmas. After over-relaxing and over-eating, with one Queen live at the Hammersmith Odeon and the other one telling us about her annus horribilis, I’d had enough.

It was 1976 and I wiled away a few hours by making a list of ten things I wanted to do during my allotted three score and ten. It was a fantasy, many years before the phrase bucket list was coined. Number five on the list was: Explore the waterways of Europe in a Dutch barge. Somehow, seeing it written down on paper made it feel possible-though in reality there was little hope. I had been married for a year and was working as an insurance agent with the Liverpool Victoria Friendly Society, collecting penny-policy premiums for £75 a week. I hated the job; the only saving grace was that I could get away with working two-and-a-half days a week. With the rest of the time I opened a small model shop and that was the beginning of 25 years of self-employment.

With a bit of hard work and more than my share of good luck, in 1998 I was in a position to buy a replica Dutch Luxemotor. Saul Trader was built by R W Davis Ltd (RWD) at Saul Junction on the Gloucester and Sharpness Canal. It was designed and constructed under the auspices of the yard’s then manager, Phil Trotter. He’s still there now, by the way, but nowadays I suppose you’d call him by some fancy title like chief exec or managing director. Not that Phil would ever court such grandeur; he’s Phil and he’s The Master. All the donkey work in running the yard is now under the control of Scragg, who back then was fresh out of school and on work experience. He certainly got plenty of that under the fatherly, unforgiving guidance of Phil, whom he dubbed The Master.

The boat was built in 1990 for the owner of the yard, Darrell, who christened it Saul Trader as a play on words of the phrase sole trader. An old sailor’s superstition decreed it bad luck to change the name of a ship, but this had seemingly not reached the continent, as every ship that changed hands over there seemed to be given a new name. Nevertheless, I was reluctant to tempt fate and Saul Trader had a certain je ne sais quoi about it. RWD had also built my narrowboat some years earlier and I’d got to know them all pretty well. Wat Tyler was completed at the end of August 1990, coinciding with the Inland Waterways national rally which was held that year in Gloucester Docks. Wat Tyler was exhibited alongside Saul Trader, at that time was still in primer with engine and propulsion but without any internal fittings. On the way back to the yard after the show, I was steering Wat Tyler when Saul Trader came powering past, driven by Phil in his typically non-PC approach, doing at least 12 knots and causing a small tidal wave to wash the feet of the fishermen and carry away their keep nets.

The yard was full of characters and I often wished I’d had the time and the ability to write a sit-com about the crazy things that went on. It would have made Only Fools and Horses look more like Mrs Dale’s Diary! There was Fat Keith, the mechanic. ‘What do you think this is Phil, Howard’s fucking Way?’ he said once, after being asked to fit some stainless steel cleats. Keith once spent several days cramped into a tiny space in the corner of the engine room on Wat Tyler sorting out the Perkins diesel-fired central heating boiler. Most of the time was spent cursing and swearing at it until it finally burst into life, sending thick black clouds of smoke belching across the yard.

‘How the hell does he ever get out of there?’ I asked Phil, over the sound of a continuous stream of blasphemy emanating from inside the boat.

‘That’s simple is that,’ Phil replied. ‘Just tell him it’s five to four.’

One of the fabricators, Paul, spent his weekends playing soldiers in the Territorial Army. He’d then spend most of the week boring everyone to death with stories of make-believe gallantry. He would demonstrate exactly how he’d shot half a dozen terrorists brandishing a piece of steel in lieu of a submachine gun and spraying the workshop with bullets shouting ‘Dah dah dah dah dah! You’re dead mate!’He once complained about one of his Saturday night compatriots: ‘He don’t take shots- I got him twice, but he wouldn’t go down.’

There was a mechanic who stayed for a couple of years. John had worked in Bristol for British Aerospace, allegedly maintaining Rolls Royce engines. Whenever a plane flew overhead, he would stand and look up, cup his hand to an ear and announce: ‘That sounds like one of mine.’ He left the yard to work for a washing machine repairer. A few months later, he paid his old workmates a visit. He was sitting in Phil’s office when the ancient machine used to wash the boiler suits started to clatter and bang and seemed on the point of exploding into fragments, potentially sending bits of underpants and boiler suits across the room. Without hesitation, Phil cupped his hand to his ear and said, ‘Ay up John, that sounds like one of yours.’

One of the young gofers, a skinny lad with a look of neglect about him, acquired the nickname Runt. His claim to fame was that he had confused the brake with the throttle on the dumper truck and driven it over the edge of the wharf, coming to rest precariously balanced over the canal. Then there was the inimitable Sean (Paddy) Care, whose talent for hand-painting boats was unmatched. Paddy did a beautiful job on Wat Tyler, but Phil complained that he always took too long. A lovable sort, Paddy was a little too sociable when it came to the pub and spent most of his evenings in The Three Horseshoes at the far end of Frampton village green, apparently the longest village green in England. He would then ride home on his bicycle, regularly falling off into the ditch and once even breaking his arm. Phil said he was lucky the ground broke his fall!

When he left the yard to work at a chipboard factory in Gloucester, he asked Phil for a reference. The first one Phil produced read something like: ‘Sean is an extremely sociable fellow as any of the regulars in all the local pubs will testify. He doesn’t do a very good job, but he always takes his time over it. He has a wonderful sense of logic and will paint the offside of a boat, balancing on the gunwale before methodically turning it round to do the other side. Sean is very keen and often takes work home with him in the evenings; he can often be seen walking home with a bundle of our best mahogany under his arm. His time keeping cannot be faulted- he is in the pub at 5.30 on the dot and never leaves before eleven. He is a very enterprising young man and has built up a lucrative trade in “imported” tobacco. Sean is always trying-often to the point of exasperation.’

Needless to say, a revised reference was produced, and Sean got the new job. On another occasion when they were launching a narrowboat, Runt unfortunately managed to leave his foot in a vulnerable place and got his toe caught under one of the rollers. The following day Sean arrived with a version of the 1960s song Big Bad John, re-written as Big Bad Toe: ‘That big old boat came rollin’ out and ran right over his toe. Big bad toe oh big bad toe.’

The sign writing was done by another colourful pair, Graham and Ann, who were from Romany stock and lived on a boat just down the canal at Fretherne. The longest serving employee was Stuart, who had been at the yard since the days when it was still owned by the Davis family. Stuart had never taken a day off in all his time there. I was told that every year he had a week’s holiday and would take his family to Barrow Hill. ‘Where’s that?’ I asked, thinking it might be somewhere warm and exotic. ‘Over there,’ Phil pointed. ‘See that bit of a mound-that’s Barrow Hill.’ It was about half a mile from the boatyard, probably 150ft high, and apparently afforded some pleasant views across the Severn to the Forest of Dean on a clear day.

Scragg, the young apprentice, was actually christened Craig; I think it was me who gave him the nickname. At any rate, I was the only one who could get away with calling him Scragg – he got touchy about it as he grew older and was given more responsibility. He first came to the yard on a work experience week aged 15, and at 16 he started full-time. I don’t think he ever contemplated working anywhere else. Scragg was brought up in Stonehouse, about five miles from Saul. He hadn’t travelled much, and he liked to play the part of the country boy but in fact he had a worldly knowledge and a quirky sense of humour. He also had a phraseology all of his own and a unique sense of insight into people’s foibles and idiosyncrasies.

Scragg would come with us on the narrowboat two or three times a year and, as far as I know, was the originator of the descriptive phrase ‘Wank Real Shit’ -particularly used when we spotted any vessel he deemed to be of an inferior breed. He could identify boats from some distance. ‘That’s a Broom 28 – they’re wank’, he’d declare. Or – ‘Just look at that fucking bow-that is wank.’ Alternatively, anything he regarded as proper would be a beast, pronounced as though the word was spelt with several ‘e’s. ‘We’ve just started building a new barge-beeeeeast.’The proud owner of one of their Northwich Trader narrowboats was obviously impressed as he actually called his boat Beast, although spelt with just the one ‘e’.

Over the years Scragg learned each aspect of boat-building- from fabrication and welding to joinery, painting, mechanics and plumbing from Phil, who he always called The Master. I don’t think he could have got a better all-round education anywhere else, and he’s still there and still learning. He was dark-haired and slim and as strong as an ox. A lot of girls found him attractive, but he lacked a bit of confidence in those days and consequently became entangled with several totally unsuitable women. For a time, he lived in a dilapidated mobile home at the back of the yard and was pestered by a strange young lady with funny eyes who worked in the local garage, where he invariably bought his lunch usually consisting of a garage-brand pie and a Kit Kat. ‘I got a stalker,’ he told me with a grin one day. ‘She won’t leave me alone. She don’t understand piss off and keeps sending me messages. That’s textual harassment, that is.’

I had known Scragg for 12 years or so and we had done quite a lot of boating together on the English canals. He always looked forward to our next bit of ‘croooosing’. For my 60th birthday, he and Phil presented me with a heavy ashtray hewn from a solid chunk of Gloucestershire stone and carved by the stonemason at Gloucester Cathedral, with three grooves set in to the top. Between the grooves in Roman-style lettering are the words ‘Wank Real Shit!’

Phil-master boatbuilder, with a wonderful eye for the finished lines of a vessel-oversaw most of the work. He had joined the company a few years earlier, having been in partnership with Mike Adkins at Stoke on Trent Narrowboats, another builder of top-quality craft. Phil says he started out constructing boats in narrowboat builder David Piper’s back garden. He survived a number of marriages and always said the only possessions he needed would have to fit into the boot of a Volkswagen Golf, ready for the next exodus. Mind you, he has a collection of more than 20 motorcycles, so a ten-ton truck would more likely be required. Saul is a wonderful backwater in a delightful area between the M5 and the meandering River Severn. Phil took to it all like the proverbial duck and settled in well with the characters and the ambience of the place. He has now been married to his lovely wife Annie for many years and has swapped the Golf for a Ford Ranger pick-up truck. I don’t think he’s got any plans to move out in the near future.

Saul Trader was based on a Dutch Luxemotor and Phil travelled to Zutphen in Holland to make drawings for a replica. It is 70ft long and 13ft in the beam. The interior is fitted out in Afromosia and teak. Afromosia is grown in West Africa and is sometimes known as African Teak because it has a very similar colour and grain. I like it for its smooth feel and luxurious sheen. This work was done by a guy called Rod who used bamboo saws, smoked strange-smelling cigarettes and considered his work an art. Rod worked for several years fitting out yachts at Falmouth. He only stayed at Saul for a couple of years, during which time he fitted out just two boats-Saul Trader and my narrowboat, Wat Tyler. The accommodation is a large double-back cabin with a beautifully rounded and panelled raised bed area right aft, a large engine room, lounge and galley, master bedroom and two further berths in a forward cabin. Each cabin had its own bathroom and shower (so basically three toilets equals three times more trouble!) The main engine is a six-cylinder Ford CS6, marinised by Lister. And there is an 8-kva Lister generator and heavy-duty battery charger, and diesel-fired central heating. Phil said there was enough power to run a small fairground.

I refer to the boat as it because a barge is an ‘it’. I don’t think a barge, as beautiful as it might be, can possibly be a she. Maybe a he perhaps-but that conjures up images of Fred Dibnah types with cloth caps and dirty boiler suits describing steam traction engines with names like Goliath or Majestic. No, I’m sorry if l am offending the romantic but a barge-a Dutch Luxemotor to boot-has got to be an it.

I bought it in 1998 and thought it was a bargain. As Phil once said about smuggled tobacco, ‘it was so cheap you couldn’t afford not to smoke.’ I suppose you can’t go far wrong if you buy something that has been built for the owner of the company. I had always assumed that, when buying a boat, traditionally you got what you saw, including the inventory. Not so with Darrell-he had stripped it bare! It was like buying a house and finding that the previous owners had taken the taps, light fittings and electrical sockets with them. It meant we had to start from scratch and chose all the crockery, utensils and bed linen to suit, but it cost the two days I’d planned for a shakedown trip on the canal. Maybe Darrell realised he’d let it go too cheaply and was trying to make a bit back. Well, it was still a bargain and I had no hard feelings but to set the record straight, several years later Darrell was shocked to learn that everything had been removed. He insisted he had left it all in situ and blamed his brother-in-law.

At that time the Cotswold Canals Trust held an annual festival at Saul, and I was delegated the job of musical director; it sounds grander than it actually was. We dubbed the festival Folk On The Water. I had always had a keen interest in the folk scene since the 1960s when I first heard Bob Dylan songs sung by a weird guy in the upstairs room of the Lord Nelson in Hastings. I was about 15 years old and spent my Sunday evenings with an illegal pint of warm bitter in the smoky atmosphere of the Old Town Folk Club. In the early 1990s, I had been mooring Wat Tyler outside a wonderful canal-side pub in Warwick called the Cape of Good Hope. Every Friday evening, they had a small folk session in the back bar and that’s where I got friendly with one of the singers, Ron Holmes. Ron had a narrowboat called Tam Lyn (a Fairport Convention song), and he pointed out how both our boats were named after songs by the folk-rock band; they recorded a song about the 14th century rebel Wat Tyler in the late 1980s.

One day I visited the yard to see how work on the narrowboat was progressing and saw that Wat Tyler had been chalked on the bare steel by one of the boatyard wags. Maggie Thatcher was about to introduce the poll tax and apparently one of the fabricators (I think it was Paul) had been ranting that no way was he going to pay, and he would rather go to gaol or the gallows etc, etc. This prompted the inscription and I immediately realised this was going to be the name of the boat. Over the years it has attracted a variety of remarks, the most frequent being ‘Ee was a Tolpuddle Martyr wasn’t ‘ee?’To which we’d reply, ‘No-he was a revolting peasant.’

Ron had formed a duo with a songwriter guitarist from Stratford-upon-Avon, Allen Maslen, and they named themselves after Fairport’s anthem, Meet On The Ledge. The festival director at Saul, Clive Field, knew of my interest in folk and asked me to organise some music. ‘Couldn’t we get that Sandy Denny bloke?’ he asked, ‘his stuff’s brilliant!’ At the first festival in 1999, we had a tent the size of a phone box and three bands. In fact, I think there were more musicians than audience. Meet On The Ledge topped the bill and went down a storm. In the afternoon I took them on the canal in Saul Trader. Ron and Allen sat on the foredeck with their guitars and Ron sang a lovely song written by Wolverhampton-based songwriter John Richards, called Honour and Praise:

On a fine summer’s morning we lay at the quay

Our holds were filled high with the treasures of the sea

So that they could be transported by men such as we

To homeland and to Queen

When the loading was done, we hoisted full sail

Prayed far good winds to guide us and deliverance from gale

And the thoughts of the crew turned to home and strong ale

As we cast off the ropes and set sail

Fight far honour and far praise

Sail the sea throughout me days

In cold ground I’ll never lay

I’d rather die on the ocean.

In the festival’s early days, Saul Trader became a sort-of green room for performers to relax before gigs, and I felt very privileged to get to know some of them as friends. In 2006 we attracted some 12,000 people, put on more than 100 acts on three stages and made £50,000 for trust funds. We also had more people on the committee than who actually attended that first event! On one occasion we had the fantastically talented Old Rope String Band, led by Pete Chaloner. The performance comprised a lot of fooling about combined with a lot of excellent musicianship. One of their acts involved a game of tennis, with violins making the sound of the imaginary bat hitting the imaginary ball. At one point the ball veered off into the crowd and landed on the head of someone in the audience. Pete asked the unfortunate to kindly throw it back and the tennis resumed. At the end of the tune, Pete asked for a cheer for the reluctant hero with the words ‘Ladies and gentlemen-big hand for this gentleman-what a tosser!’ I was roped in as a stooge for another part. At a given signal from Pete, I had to rush on to the stage with a piece of paper and interrupt the performance to announce there was a vehicle on fire in the car park. As instructed, I read out the registration plate two or three times and, of course, there was no reaction. I then repeated ‘Victor Hotel Romeo 729-a white Transit van’, at which point Pete and fiddler Jo Scurfield dashed off stage in a cloud of dust leaving the third member, Tim, to recount some shaggy dog tale about his favourite childhood teddy bear. After about ten minutes Pete and Jo returned, their shirts torn, and faces charred with soot! Tragically Jo was killed some months later by a hit-and-run driver in Newcastle, and the band never recovered.

Another band that made a big impact were The Rollin’ Clones tribute. Their last number was You Can’t Always Get What You Want and the singer, Mark, recruited several young ladies onto the stage to join in the chorus. At the end as they were cheered off, Mark stood at the top of the steps and presented each of the girls with a mini Mars Bar-a nice touch. A few years later, an excellent band called Bluehorses made a live DVD recording at the festival, performing a version of the Deep Purple classic but renaming it Folk On The Water. After an arousing chorus of applause for an amazing solo, the lead singer and electric fiddler, Cardiff-born Lizzie Prendergast- thigh-length boots, short skirt and long black hair -sidled sexily up to the microphone, and said in her sultry voice, ‘Classically trained, see.’

Bob Fox, who has made a bit of a name for himself as the song man in the War Horse productions, had his set interrupted when a bull jumped into the canal and started swimming frantically to Sharpness. When I asked Bob to do another appearance a few years later he said, in his inimitable Wearside, ‘Only if you’ll get that bull to lollop into the cut again.’ Among other notable performances was Sid Kipper, who stopped mid-song and refused to go on unless a certain member of the audience turned off his mobile phone or ‘pissed off out of it’. The lovely Fred Wedlock, compering for John Tams and Barry Coope, was drowned out by shouts for more from the audience. He told them, ‘All right-this is the awkward bit when I have to go back there and ask him if he’s got a short one.’ The lead singer of Bristol-based Irish band Celtic Five, David Foggarty, shocked the audience after peppering the set with more than a few Irish expletives. ‘I must apologise to anyone who has young children here in the audience-you irresponsible feckin’ bastards,’ he said. Well, it was after the watershed! We had some great evenings at Saul over the years with the likes of Nancy Kerr and James Fagan, Last Night’s Fun, Kevin Dempsey, Little Johnny England, Wild Willy Barrett, Filska, Les Barker, Oysterband, Sara Jory, Shooglenifty and last but not least, the mighty Show of Hands. We were especially lucky to arrange a rare appearance by the iconic 1970s folk-rock band Decameron with the legendary singer guitarist Johnny Coppin, and the gravel-voiced vocals of Dave Bell, who opened the set with the appropriately entitled Say Hello To The Band.

Unfortunately, the festival suffered badly from flooding just four days before the start in 2007 and had to be cancelled, a tragedy from which it never really recovered. Clive had done a sterling job and I think in the end it all got a bit too big for its own good. The final event was held in 2008, and since then I’m often asked by people with fond memories when it’s going to start again but somehow, I don’t think it ever will. It was fun while it lasted but ran its course.

If you enjoy this excerpt, you can read more in We Don’t Go Far, But We Do See Life.

For a limited time only, get the book for free with any print subscription to Towpath Talk (UK only).