Jonathan Mosse’s monthly look at freight development on the inland waterways.

IN MOST people’s minds, ports have strong coastal affiliations and are unlikely to be poked tidily away up rivers or canals. But 200 or more years ago, the fabric of commerce between Britain and the rest of the world had a very different weave from the pattern we are familiar with today, particularly before the invention of the container or ‘box,’ as this ubiquitous trading device is often referred to.

To get some idea of scale, we can look at the dimensions of the Forth & Clyde Canal running across the Central Belt of Scotland, connecting the River Clyde on the west side of the country with the Firth of Forth on the east. Built to save vessels crossing the Atlantic from the Americas from also having to traverse the Pentland Firth (on the northernmost coast of the country) its depth was just a fraction under three metres, with a lock gauge of just six metres wide by 21 metres long.

Less ambitious, but of similar importance, barges trading up and down estuaries on eastern and western seaboards of England and Wales also penetrated well inland, so that when narrow- and (to a lesser extent) broad-canals started to appear, a viable interface was required in the form of transshipment facilities for onward travel of imports or the outflow of exports.

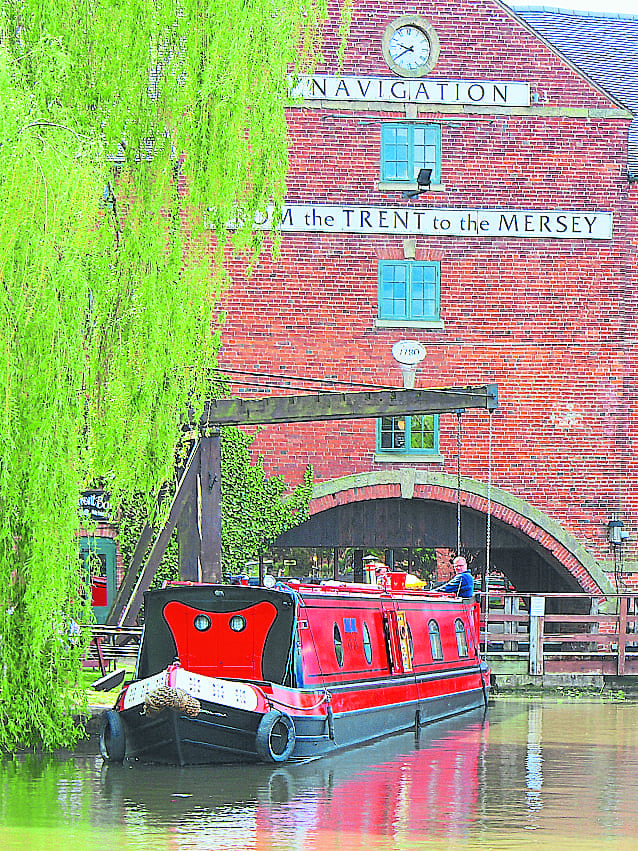

What this added up to was the establishment of inland ports or the expansion of existing examples – such as those at Exeter or Chester: a phenomenon that has only recently started to be recognised again in the form of the Historic Inland Port status, recently conferred on both Stourport-on-Severn and Shardlow, alongside their two aforementioned predecessors.

From the Middle Ages onwards this country’s economy began to lean heavily on worldwide trade and among its principal workhorses were the barge-craft that evolved to serve the specific needs of the different estuaries around our coast.

While the inland port of Chester started life able to accommodate the then-transatlantic vessels, later followed by Exeter, Shardlow developed as an inland transshipment port to move cargo between Humber keels plying the Trent and canal barges, just as Stourport fulfilled a similar role with Severn trows as an interface between river and the Staffs & Worcester Canal.

Interestingly, Chester and its significance as an international port easily pre-dates the emergence of Liverpool (and other Mersey ports from that era) and, before the Dee gradually silted up, handled by far and away more tonnage than everywhere else in the North West put together. On a more local basis, Mersey Flats would have been the workhorses of the port.

The five-mile Exeter Ship Canal was opened in 1566. Built at the modest cost of £5000, it was initially only able to accommodate craft carrying 16 tons. Following improvements, 100 years later, this increased to 60 tons and at the turn of the 18th century, by dint of various further enhancements, this had risen to 150 tons. So now two inland UK cities enjoyed the benefits of direct trade with the rest of the world.

On the south-east side of the country, Thames barges bore the brunt of the local estuarine and coastal work, but also regularly plied their trade as far afield as the Tyne to the north and beyond the Exe (and Exeter) in the South West. All in all, this amounted to a tight-knit integration of waterborne trade, serving large tracts of the country.

Ultimately, the question to be answered is ‘what can this intriguing piece of waterways history contribute (if anything) to the true multi-modal transport debate of today?’ Given that moving goods by water, in appropriate craft – whether in deep estuaries or properly dredged canals – on a per ton basis, incurs but one-fifth of the energy consumption of road haulage, it is clearly a desirable way to proceed in the face of climate change and global warming.

However, its potential success clearly lies in forms of streamlining undreamed of by its forebears, where labour was cheap and plentiful. Road haulage has its swap bodies, while international freight has been changed out of all recognition since the ‘box’ took over.

Inland waterways transport, more recently left standing on the sidelines, might just want finally to come to the party bearing the gifts of both, recognising that, in the grand scheme of things, the size of the overall investment required to make this all work is small relative to the possible gains to be made from its contribution towards achieving a net zero economy.