Originally promoted as a canal, the railway to West Croydon has had five different methods of traction. This article by Edwaard Treby was first published in The Railway Magazine in October 1967.

IN 1801, Acts of Parliament were passed for the construction of a canal from the Grand Surrey Canal (also authorised in 1801) at Deptford, to Croydon, and a horse-drawn railway, the Surrey Iron Railway, from Wandsworth to Croydon. The original proposal was a canal from Wandsworth to Croydon, tapping the water of the River Wandle, but strong opposition from the mill owners on the river was encountered. The Surrey Iron Railway was opened in 1805 and the Croydon Canal in 1809. Then having 7,000 inhabitants, Croydon was the first town in Britain to be served by competing forms of transport for goods traffic. The subsequent history of the canal and its railway successors is notable for a number of other “first occasions”.

The Croydon Canal, 9 1/4 miles long, ran through New Cross, Brockley, Sydenham, Anerley and Croydon Common, terminating by the main London Road at West Croydon. From Brockley to Kent House the canal ran close to the River Ravensbourne. It cost £127,000, and had 28 locks, 26 of them in the first 2 3/4 miles to Forest Hill, a rise of 155 ft.; the next 5 1/2 miles were level and near Croydon were two more locks, making a total rise of 167 ft. from Deptford. The canal was fed by reservoirs at Sydenham and Norwood and had a pumping station at Croydon. Difficulty was experienced in maintaining the water supply in the higher sections. John Rennie and Ralph Dodd were the engineers for the canal and William Jessup for the S.l.R.

From London the traffic by rail and canal was principally coal, while from Croydon, timber, lime, stone and agricultural products were carried. Although the Croydon Canal had introduced traffic to the Grand Surrey Canal and the adjoining docks, friction arose between the two companies, because of dock traffic interfering with canal boats. Neither the Croydon Canal nor the Surrey Iron Railway ever paid a dividend of more than one per cent. In the vicinity of Forest Hill, Sydenham and Anerley, the Croydon Canal was a source of great delight to local people, for boating, fishing and walks along the towpath amidst unsurpassable scenery. Boats could be hired and, from 1814, the company sold angling licences at a guinea each. Now that the amenity and recreational value of our waterways is better known, largely thanks to the efforts of such bodies as the Inland Waterways Association, the enterprise shown by the Croydon Canal is worthy of recall.

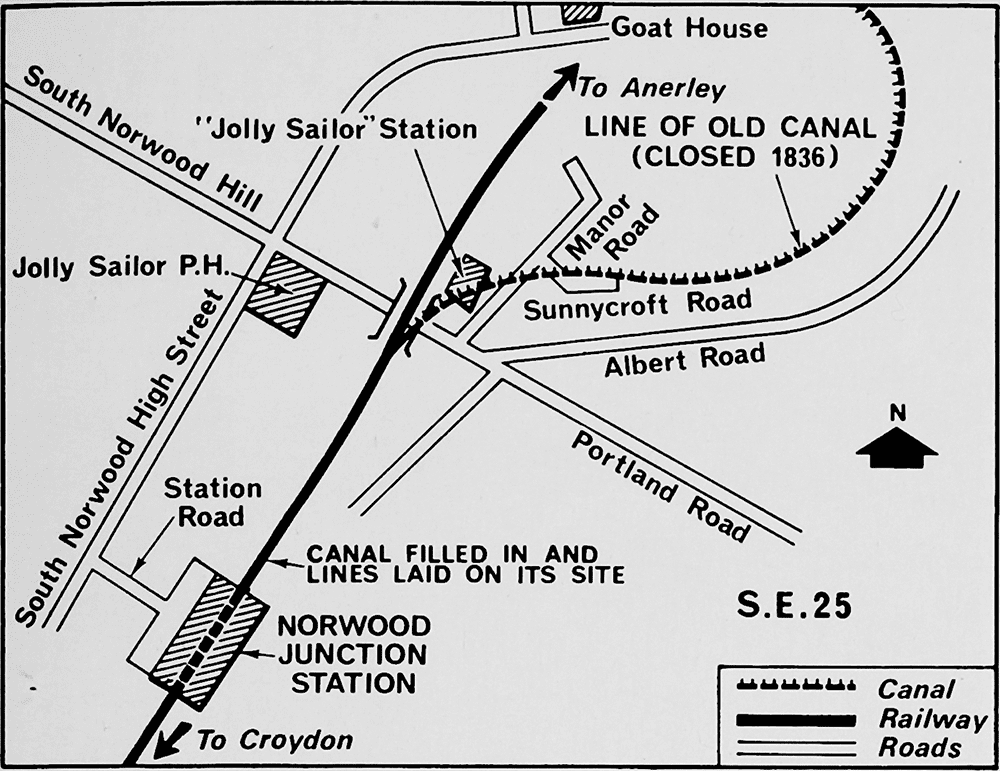

In 1834, Joseph Gibbs surveyed a new railway to Croydon, which, where possible, would use the canal bed. Following negotiations between the newly-formed London & Croydon Railway Company and the canal company, the former by a quaintly-phrased Act of Parliament was compelled to purchase the canal in July 1836. The price, as fixed by an independent jury, was £40,250 plus 1s. for non-existent profits. The canal closed in 1836, the first waterway in the London area to close for navigation, although the newly formed railway company realised that anglers would bring revenue as shown by an announcement in “Robinsons Railway Directory” for 1840 thus: “Marquees are erected in the Wood close to the Anerley Station and Parties using the Railway will be permitted to angle in the adjacent canal which abounds in fish.” The Surrey Iron Railway, after passing into the hands of other railway companies, was abandoned in 1846.

Remains of canal

Traces of the old canal remain. At the junction with the Grand Surrey Canal, a short length of the Croydon Canal and an adjacent basin still used commercially are intact. This stretch can be seen when travelling along the Central Section of the Southern Region on the up side. As late as the 1920s, two of the original lock-keeper’s houses stood in Shardloes Road, Brockley, S.E.14, slightly to the east of the present railway. In Betts Park, near Anerley Station, a stretch of the canal remains and is now an attractive tree-lined length of ornamental water with the fountains down the centre. The largest surviving fragment of the canal company’s property is South Norwood Lake, originally one of the feeding reservoirs. It lies alongside the Crystal Palace-Birkbeck line and is a favourite haunt of fishermen, thus recalling the attraction which the canal had for anglers in the early days. At Croydon little remains, although the path alongside the railway near West Croydon Station follows the course of the original towpath. In the grounds of an adjacent flour mill, a piece of water, originally a canal dock, survived until the present century but disappeared on rebuilding of the premises. A bridge known as “Brick Bridge” near West Croydon Station originally spanned the canal. The bridge has been widened but the parapet on the station side is the original one.

The London & Croydon Railway, the second line in London after the London & Greenwich Railway, cost £615,000 to construct. It ran from the site of the former canal basin at West Croydon to Corbetts Lane, Bermondsey, a distance of 8 3/4 miles against 9 1/2 by the canal. Beyond Corbetts Lane, the L.C.R. paid tolls to use the L.G.R. viaduct into London Bridge Station. The L.C.R. was officially opened on June 5, 1839. The company’s original headquarters became the stationmaster’s house at West Croydon which lasted until the rebuilding of the station in the 1920s. At London Bridge the L.C.R. had its own station to the north of that belonging to the L.G.R. At the junction of Joiner Street and Tooley Street, S.E.1, the original facade of the L.C.R. 1839 station can still be seen. At the request of the Grand Surrey Canal Company, a clause was inserted in the Croydon Railway Act stipulating that cranes be provided at a point known as Coldblow Wharf, adjacent to the junction of the Croydon and Surrey Canals. Railborne freight from the L.C.R. could thus be transferred to the Surrey Canal and reach the Thames without incurring the L.G.R. tolls.

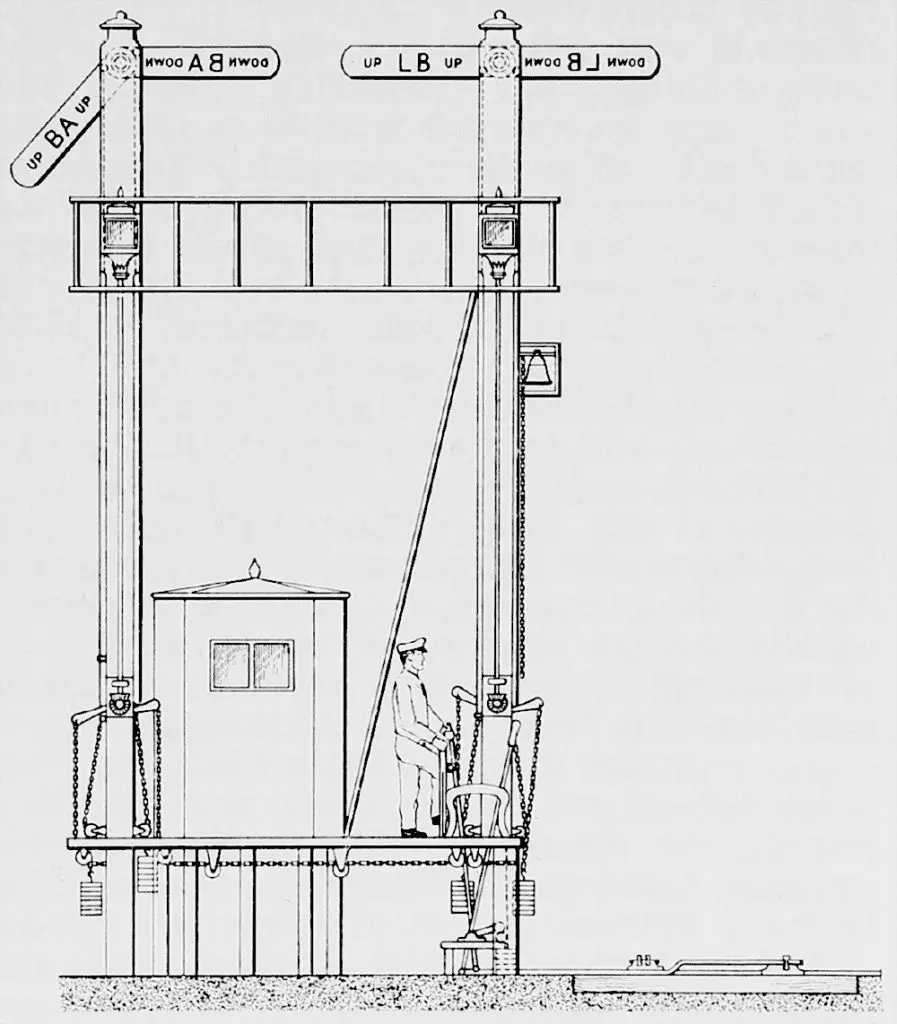

Intermediate stations were New Cross (now New Cross Gate), Dartmouth Arms (now Forest Hill), Sydenham, Penge, Anerley and the Jolly Sailor (now Norwood Junction). Apart from the 1-in-100 gradient in cutting from New Cross to Forest Hill, a costly section to build which corresponded to an average rise of 5 1/2 ft. for each of the 26 looks on the canal, the route was fairly level. Corbetts Lane was among the first railway junctions anywhere and the signalbox known as the Corbetts Lane Lighthouse was the first in the world. In 1842, the L.C.R. Engineer, Charles Gregory, installed the first semaphore signal at New Cross.

Six of the original eight Croydon locomotives were built by Sharp, Roberts in 1838 and 1839. Five were of 2-2-2 wheel arrangement with 13 in. X 18 in. inside cylinders and 5 ft. 6 in. dia. driving wheels. These were Nos. 1, Surrey, 3, Sussex, 4, Kent, 5, London, and 8, Victoria. No. 8 was later renamed Syderzham. For banking duties up the incline between New Cross and Forest Hill two 0-4-2 locomotives were used, Nos. 2, Croydon, and 6, Archimedes, built in 1838 and 1839 respectively by G. J. Rennie, with 13 in. X 18 in. horizontal outside cylinders and 5 ft.mdia. coupled wheels. The eighth locomotive was No. 7, Hercules, built 1839 by Sharp, Roberts, with 14 in. X 18 in. inside cylinders and 5 ft. dia. driving wheels; it is believed to have been an 0-4-2. In 1842 the rolling stock of the L.C.R. and S.E.R. were used in common and managed by a Joint Committee. In March, 1844, the London & Brighton locomotives came into the pool, but on January 31, 1846, the Joint Committee was abolished and the stock divided between the S.E.R. and L.B.S.C.R. as the L.C.R. was then on the point of dissolution. The New Cross Roundhouse was one of the first in Great Britain.

Atmospheric traction

Besides its local trains, from the 1840s London & Brighton and S.E.R. trains used the L.C.R. metals from Norwood northwards. These companies disliked paying the L.C.R. tolls, just as much as the latter objected to those of the L.G.R. Much congestion ensued and to overcome the difficulty the L.C.R. decided to adopt atmospheric traction, initially between Forest Hill and West Croydon, opened for public service in 1846. During trials conducted by the patentees, Clegg & Samuda, on a line leased from the West London Railway near Wormwood Scrubbs, speeds up to 70 m.p.h. were reached. A slotted tube was laid between the rails and the leading carriage (there was no engine) connected to a piston in the tube, the slot being closed by a leather flap. To exhaust the air in front of the piston and so propel the train, gothic-style pumping stations with chimneys concealed in ornate towers were erected at Forest Hill, Norwood and Croydon. In February, 1847, the atmospheric line was extended and trial running only took place between Forest Hill and New Cross, where a fourth pumping station was built. The greatest problem was keeping the pipe airtight, as the composition which sealed the leather flap melted in hot and froze in cold weather. As conceived, atmospheric trains could not be worked through junctions or crossovers (are we yet thinking of monorails as networks or merely individual lines?). At Norwood, the single atmospheric line had to cross the main-line tracks, which necessitated the construction of Britain’s first railway flyover in 1845. In highway construction, apart from isolated examples such as Holborn Viaduct opened in 1869, the flyover idea seems to have remained dormant until the present motorway era.

Although extensions to Epsom and London Bridge were planned, the atmospheric line, which had cost £500,000, was converted to locomotive haulage in May, 1847. The Forest Hill Pumping Station, used for many years as a milk depot, was destroyed by a flying bomb in 1944. In 1906 and during reconstruction at West Croydon in 1933, when the last vestiges of the L.C.R. 1839 station disappeared, atmospheric pipes were unearthed.

Apart from Brunel’s ill-fated venture on the South Devon Railway and the railway between Kingstown (now Dun Laoghaire) and Dalkey in Ireland, which according to contemporary reports was moderately successful, atmospheric traction, also on the Clegg & Samuda system, was adopted on the Paris to St. Germain-en-Laye Railway, the first line in Paris. Before completing the steeply graded final section, the line terminated at Le Pecq below St. Germain. Originally it was intended to use atmospheric traction, not only on the final 1-in-29 section but also between Nanterre and St. Germain, a distance of 1/2 miles. Atmospheric traction commenced in 1847 but only between Le Pecq and St. Germain. Two of the three pumping stations were never used. Before the introduction of atmospheric traction, L’Hercule, a six-coupled engine more powerful than its predecessors, had entered service and could tackle the gradient to St. Germain. Steam traction was used between Paris and Le Pecq and occasionally to St. Germain. Because of heavy maintenance costs, particularly the problem of keeping the pipe airtight, atmospheric traction was abandoned in 1860.

Much in common

The Paris to St. Germain and the London & Croydon Railways have much in common. Both started as local lines and became part of large suburban networks, and in the 1920s both were electrified on the third-rail d.c. system, although a section of the Croydon line was originally electrified on the a.c. overhead system adopted by the L.B.S.C.R.

In 1846, the L.C.R. amalgamated with the L.B.R. to form the London, Brighton & South Coast Railway. Although space precludes a description of subsequent development, it is worthy of note that in pre-grouping days S.E.R. (and latterly S.E.C.R.) trains shared the tracks between London Bridge and Norwood Junction and on to Redhill but between London and Croydon their trains called only at New Cross, Forest Hill and Norwood Junction, which still have platforms on the centre tracks or fast roads. Before electrification of the East London Line in 1913, the Great Eastern Railway operated a service from Liverpool Street to New Cross and East Croydon. The section of the present line between Gloucester Road Junction and West Croydon Station has been a canal and as a railway has had five different methods of traction: steam, atmospheric, overhead a.c. electric, third-rail d.c. electric, and now diesel for goods trains.

In conclusion, the author wishes to thank the Archivist, British Railways Board, the Public Relations & Publicity Officer, Southern Region, and Mr. P. W. Sowan of the Croydon Natural History & Scientific Society for their valuable assistance. For information on the French atmospheric line, the writer is indebted to the Press Department of the S.N.C.F., Paris.